Sample Biographies

Colin McAlister

Words by Kathy Stewart from Unique Biographies

It was fun working with Colin, assisting him in publishing his book ‘It’s All About Me’. The tongue-in-cheek title reflects Colin’s light-hearted personality, while the content of the book reflects his organised and methodical approach to collating a lifetime of memories and experiences.

Colin wanted to document his life story for his wife and his sons. I know they will be impressed reading about Colin’s beginnings as a young boy in the country, helping his Mum with the chores and improvising wonderful childhood pastimes, through to his passion for music during the pop revolution of the 1960s, and his service in the Royal Australian Navy.

The skills Colin gained from his country roots drew him back to the land after his Navy service, though he later settled with his family on the Gold Coast and became involved with various sporting clubs.

Now that Colin has completed his biography, he is inspired to write an additional book, perhaps aptly titled ‘More About Me!’ Colin has written a fabulous account of his life and I’m so pleased that after his experience with Unique Biographies, he’s already considering other anecdotes and stories that he would like to share. The writing process always promotes further conversation, so I’m confident that his family will also enjoy his future work.

I wish Colin, his family, and friends, lots of fun and reflection as they read and enjoy ‘It’s All About Me’.

Excerpt from ‘It’s All About Me’ by Colin McAlister.

I signed up with the Royal Australian Navy for nine years. Recruit training was held at HMAS Cerberus in Melbourne for three months in the middle of winter. We had to start at five o’clock in the morning, assembled in the parade ground in shorts, a singlet and runners. We would be sent off for a one to three mile run, then back to the parade ground for half hour exercises including push-ups, sit-ups, star jumps and burpies.

Everywhere you went on the depot was at double time (jogging). If you were caught walking, you would be punished. Punishment for any offences consisted of either extra duty in the galley, washing dishes and pots or mopping floors. If you were given a harsher punishment, you had to roll up your bed mattress, put it on your shoulders and jog around the parade ground port arms (holding your rifle above your head horizontally) until you were told to stop. The 303 rifle used in World War II weighed approximately 6–7 kilos. We trained seven days a week for three months.

Most of the recruits joined the Navy straight out of school, whereas I was twenty-one years old when I joined up. Some kids couldn’t cope with the discipline, which was pretty harsh at times. They would be discharged and sent home.

On completion of my recruit training I was drafted to HMAS Albatross: Fleet Air Arm, in Nowra, New South Wales. You’ll find my name on a plaque on the Fleet Air Arm Wall of Service at the HMAS Albatross Museum. My name is also displayed on the wall of Remembrance Walk in the town of Seymour, Victoria, just outside of Melbourne.

At HMAS Albatross, I completed a three month course in the safety equipment branch. My job at HMAS Albatross in the safety equipment branch was to maintain and service all safety equipment including: parachutes, flying clothing, life rafts, oxygen masks, emergency radio beacon equipment, helmets, rations in emergency packs, and several other pieces of equipment associated with the aircraft pictured.

Part of my job also involved instructing pilots how to escape from their cockpits if they landed in water. This was carried out in a simulator thrown in the deep end of a swimming pool with the pilot in it. I also oversaw parachute training on a flying fox and instructed pilots on how to survive at sea and in the bush. On board a ship, it was my role to maintain and service life rafts and life jackets and instruct the crew how to operate safety equipment.

While still working at HMAS Albatross, I was in a Royal Guard that went to Canberra to greet Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia, when he visited Australia. In 1969 I was drafted to HMAS Vendetta Daring Class Destroyer. She was in refit at HMAS Kuttabul Garden Island in Sydney.

We spent seven months off the coast of Vietnam. A small insight into this period: while on the gun-line (800 metres or less off the coastline) we would work six hours on and six hours off, twenty-four hours a day for two to three weeks straight. During that six hours off, you had to eat, wash clothes and try to get some sleep, all while the guns were firing. A spotter aircraft (helicopter or Cessna) would find the targets and radio to the ship where they were. The ship was always at anchor when firing (for accuracy), and was therefore vulnerable.

We would get three to four days R&R (rest and relaxation) after two to three weeks on the gun-line, mostly in Subic Bay American Naval Base. All of that time off was spent partying hard in Olongapo City, just outside the Naval Base. Just through the main gates of the Naval Base was a stretch of road half a kilometre long with 450 bars, 4,500 bar girls and a VD clinic (venereal disease) every couple of hundred metres on both sides of the road.Kids on the street would sell baby ducks to the sailors and marines to feed an ‘alligator’ which was in a big opened pond half way down this stretch of road. Then it was back to the grind on the gun-line.

Returning to Australia, all service personnel that served in the Vietnam War were treated like outcasts by the Australian community, tagged as ‘baby-killers’ and even spat at. I couldn’t understand that. We were casualties of a war nobody understood. I found it extremely difficult to adjust back to a normal lifestyle when I got home. I still have issues today that I have learned to deal with, in my own way. It took the Australian government thirty years to recognise our contribution to the Vietnam conflict. Since then, I have marched in ANZAC Day in Brisbane every year alongside my mates.

Merle Carmichael

Words by Kathy Stewart from Unique Biographies

We have had a wonderful journey with Merle, documenting her experiences through her early life and involvement serving her country during WWII, to the many achievements in her professional career.

Life has many wonders and joys for us to celebrate, but it also brings a degree of pain, which we all need to learn to cope with. Losing a partner of many years: the person you’re dedicated to, the person you love, understand and cherish, is so difficult, though we can all learn lessons from observing how people manage their loss. Merle, at age ninety one, has lost her beloved husband Bill to Alzheimer’s disease. However Merle celebrates Bill every day by acknowledging his good character, keeping his memory with her by speaking of him, and now the ultimate recognition, documenting their life together.

Bill–and both Bill and Merle’s parents–would be so proud of Merle, not just because she has honoured them by writing her biography, but because she is a lovely, kind, compassionate, and sensitive person.

Merle has a wonderful sharp sense of humour and we have very much enjoyed the process of writing her life story. The books we create at Unique Biographies are quite beautiful: the paper and printing is such extraordinary quality and the content is precious. The best feeling in the world is hearing stories of how the books are received by our client’s family and friends. Although it is an amazing feeling to hold a completed biography in our hands and witness the admiration of our clients when we hand over their books, I admit to the bittersweet feeling when a project ends.

The process of writing a biography is exceedingly enjoyable and brings immense satisfaction to both our clients and ourselves. I feel so happy for Merle that she can tick off writing her personal biography from her ‘bucket list’. It has been an absolute pleasure to have assisted her to achieve her goal.

Foreword from ‘Through The Years’ by Merle Carmichael.

Merle is an extraordinary woman with an endearing sense of humour. Through the expertise of her father and husband she gathered extensive knowledge of the building industry and demonstrated considerable business acumen. Purchasing land, assisting in the organisation and operational processes of building projects, as well as running and supervising many investment enterprises have been just some of Merle’s outstanding accomplishments.

She is extremely fulfilled to have served her country in the WAAAF during World War II, and is fiercely proud and appreciative of her family. Her devotion was especially lovingly displayed during her beloved husbands battle with dementia. Merle and Bill were a team devoted to the development and well-being of their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Merle and Bill’s dedication to the Rotary organisation and other community organisations, the establishment of The Carmichael Walk, and of course the building and operation of The Carmichael Hospital is a credit to their selfless characters. Their determination to give service to the community is a true legacy.

Excerpt from ‘Through The Years’ by Merle Carmichael.

This is a small sample from Merle’s biography. It is just one section of a comprehensive narrative of her life.

All new recruits into the WAAAF had to undertake a rookie’s course. My initial training in 1941 was dispensed from the Bankstown Airbase, and consisted of drills, marching on the tarmac, lessons in making a bed the correct way and basic training army skills. During this time, I slept in a long barn-style building with twenty others, on a wire frame folding camping bed with a straw mattress.

This period was quite difficult and extremely strict. It was unlike anything any of us had ever experienced. We had to wear a uniform to work, complete with stockings, hat and gloves, and were expected to be impeccably dressed at all times. They had positioned the Chief Clerk’s office nearby, so we all had to walk past and he would prop his door open to inspect our uniforms.

In the dormitory, there was a strict ‘lights out at 10pm’ policy, though I remember one evening, one of the girls had been given a fruit cake for her birthday. We had to wait for the inspection team to pass before we opened the door, just slightly to let enough light in to cut the cake by moonlight.

After training, I was accepted into the very first intake of the WAAAF and was initially housed in unit accommodation at Double Bay with three other girls. Double Bay was, and remains to this day, an upmarket suburb. Many of the homes around Sydney–especially those situated on the harbour–had been commandeered by the army to house recruits. My poor mother was beside herself! Dad was away with the RAAF and her only daughter had also enlisted. She actually came to visit me in Sydney at this point, just to make sure that I was ok.

From Double Bay, we were channeled into the fields that best suited us, according to prior experience, qualifications and aptitudes displayed in training. In addition to the much needed telegraphist roles, women became armament workers, electricians, fitters, flight mechanics, fabric workers, instrument makers and meteorological assistants, and worked in fields as broad as clerical, medical, transportation, catering, equipment, signals and radar. Over 700 women held commissioned rank and worked in a variety of administrative, technical and professional tasks.

I served as a Teleprinter Operator at the RAAF Headquarters at Point Piper in Sydney and eventually, at the St Kilda Road Barracks in Melbourne. This role involved sending and receiving secret coded messages by landline. This was a very difficult, stressful and emotionally challenging role. We were actually limited to the length of time we could work on the teleprinters, because we were in constant receipt of messages relaying the number of deaths and casualties recorded.

Some of the machines were ciphers, which were scripts of just 5 letters. It was important to be accurate and precise at all times so that the right messages were received. The exacting nature of the role was incredibly taxing, especially for young women of just seventeen or eighteen years old.

Outside of work, it was the norm to carry a gas mask at all times, and daily electricity black outs were commonplace. We would travel to and from work on public transport, often in complete darkness. Wardens patrolled the streets to ensure that street-facing windows were uniform and did not emit any light.

I was on duty at Point Piper the night Japanese submarines entered Sydney Harbour below our headquarters.

Christine Day

Words by Kathy Stewart from Unique Biographies

Christine found Unique Biographies at a time when she was experiencing personal crisis and ill health in her family, despite the fact that is still relatively young in age. Sometimes documenting your life story can help to place your feelings and life philosophy in perspective so it was a wonderful experience to help Christine write her life story. I have great admiration for her ability to accept and understand the flow of life and her interest in all things spiritual and metaphysical.

The experience of growing up in a small religious group in the country region of New South Wales shaped Christine’s morals and outlook on life. Although she had many fun times and felt dearly loved by her family, she experienced betrayal and lack of support from the group when she needed it the most. Seemingly, it was unforgivable if members of this group were unable to exactly fit the stringent code inflicted upon them. This was devastating for Christine to discover as she had put so much unconditional faith in the teachings of the group. Family and community were interwoven in the religion and Christine’s life was changed as she was forced to reconsider her views.

Life can deliver many challenges. Christine's spiritual journey has not been her only trial, but she has faced her challenges valiantly, learned many lessons along the way and gained personal growth, to the extent which many of us can only aspire to.

This is a sample from Christine's Biography.

It is just one section of a comprehensive narrative of her life, trials, tribulations and growth.

Questions of Faith

The combination of physical trauma and emotional turmoil allowed me to reflect on my own life, my own achievements and beliefs. For the first time, I was able to assess my life from a different perspective.

My faith in everything that I had built up was shaken and I really felt that God wasn’t answering my prayer for Allan to come home. I realised that I needed to re- evaluate my life and my association with the No-Name Fellowship. For a variety of reasons, I decided that I no longer wished to attend the meetings.

Then, upon my return to Australia without Allan, I was essentially ostracised; nobody wanted to know me. The questions, rumours and innuendo were rampant at the meetings, when all I truly needed at that time was love and support.

I was shocked to find that such a supposedly loving, caring and supportive group of people could not comprehend my emotional trauma and needs at that time. The worst of human nature was on display, in direct opposition to their own teachings, and it was very difficult for me to accept and understand such behaviour.

There was no support network available for me, no counselling, no marriage guidance, and no qualified people to discuss my situation with. I was left to traverse any challenge on my own with prayer and internal reflection the constant and only answer.

Part of the teachings of the group include that you are tied to your husband or wife for life. If either party left the relationship, you were still married in the eyes of God and were to remain single for eternity. In God’s eyes, to remarry is to commit adultery because your husband is still alive. This seemed incredibly unreasonable in a circumstance like mine, where I sincerely wished to reconcile with my husband, but was not able to, due to no fault of my own.

At this time of turmoil in my life, I was faced with an internal struggle of where to place my faith, though it is difficult to question the norm when you have only ever lived and experienced one way of life. I began to doubt whether the Fellowship was ‘the truth’ or ‘the way’ as they had taught. I started to wonder whether everyone in my family was in fact wrong in the choices they had made throughout their lives. What if there was more than one truth? What if there were other, equally poignant and significant ‘ways’ of living and loving God? Such questions were, and continue to be, very challenging for me to process.

In saying that, I did meet some wonderful people through the meetings, many of whom were sincerely generous, kind, giving, moralistic and upheld high standards. They genuinely followed the word of God and deserve only the best. To face turning away from the Fellowship and these fantastic people led to great despair and depression. Upon my return from Switzerland and after the news from Allan, I felt incredibly alone, like I had been dropped in the wilderness.

Telling my stepmother that I wasn’t going to attend the meetings anymore was a huge turning point in my life, and perhaps one of the only decisions I had, at that point, ever made solely for myself. She was devastated when I left the group. As her beliefs were so strong, I really felt that I had disappointed her, which was never my intention.

The contradiction between teachings and real-world action is evident in any religious group, or any circumstance involving power and influence. I have since heard the analogy that going to the meetings was like a wheel; those in the centre stay clean, while those on the outside experience all the mud. I had quite an incredible revelation when I realised, after leaving the group, that we weren’t worshipping God or Jesus at the meetings at all; we were worshipping the workers! It was their job to break the will and shatter the spirits off their followers, which then enabled them to impart their teachings to the group.

While I feel disappointed that people I grew up with—who had been like family to me throughout my life—no longer contact me since I have left, I can now clearly see that blood really is thicker than water. With any congregation of people, it is certainly wise not to bear your soul. I have learned to be very careful whom I trust and have since gained enough confidence and self-esteem to be my own person. My children and their well-being is the only thing that truly matters.

Despite my initial grief and sense of loss, I also felt a great freedom in separating from the Fellowship. I now feel much less naïve or susceptible to accepting others words as truth. I am more open and insightful with no inhibitions or need to make excuses for my life, my actions and my beliefs. The meetings were so insular and closed off from the rest of the world; now, being away from that limited experience, I feel that new life experiences are much more accessible.

I have since reconciled my thoughts and feelings and do not have any bitterness towards anyone throughout my life. The challenges I have faced have led me to accomplish many things that I wouldn’t have otherwise done.

Image: Christine as a child.

David and Phyllis

This is a sample from one of our client's Biographies relating to time spent in an orphanage as a child.

This is just one section of a comprehensive narrative of Phyllis' life.

Image from David and Phyllis' wedding day, May 12, 1956 in Wahroonga New South Wales.

The Riversdale Orphanage that we were to attend in Riversdale, Lancashire, did not accept children under seven years old, so when Margo turned seven, she left the Tadgell home and I followed two years later. Just two years after I arrived the orphanage was closed due to financial difficulties and both Margo and I were moved to the Princess Alice Home and Orphanage in Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham.

Princess Alice was run by a charity group, and again, we were always treated very well there. I’m not sure how the orphanage was funded or even if my extended family contributed financially to our stay there. Margo and I were always shielded from such discussions and had little contact with anyone outside of the orphanage. While at Princess Alice, I do recall receiving twenty pounds from someone, presumably a family member, and my grandmother once sent me a toy farmyard, though I never had regular contact with her, or any of our extended family.

Princess Alice was segregated by gender. Males and females were restricted to certain houses and common areas on the grounds. As a young girl wanting to meet new friends, I once got into trouble for walking in the woods with a boy that I had met. It was all very innocent, of course, but I had to scrub the floors as punishment for breaking the segregation rules. Discipline was enforced, though the orphanage employees were always fair, respectful and well regarded.

I am sure that many of the children in the orphanage had suffered through tragic or abusive circumstances, though this was never discussed, not with the staff or with the other children. From my perspective, without having known any other life, we were all happy young children, engaged in the same activities and enjoying the same privilege and lifestyle as any other child in England! Many may consider that mindset stemmed from a youthful naivety, though in hindsight, despite some monotonous rules and regulations, we were always cared for appropriately, and in some cases, perhaps even better than our non-orphaned counterparts. The economic and social climate of the time was quite dire, especially in the post-World War I period, however, we always received the relevant dental and medical care and were provided with immunisations and preventative health care measures.

We ate in a communal dining room and often had to assist in the preparation of food on a roster basis. Our meals were basic, and we were expected to eat it all, whether we enjoyed it or not! We slept in dormitories, with approximately four or five children to a room. Our beds had to be made up properly at 6am every morning and we had to turn our mattresses each day. I have clear memories of decorating our rooms at Christmas time and competing to win prizes for the prettiest, most unique decorations. Girls and boys were brought together for Christmas lunch and we always received little sweets and treats at this time of the year.

Our weekends were spent in Sutton Park, just a short walk from the Home on Chester Road. We also played in the local woods, picked blackberries and bluebells from the fields or paddled in the streams. I loved skipping as a child and could skip outside for hours at a time. Other enjoyable extracurricular activities included dancing around the maypole and singing.

Roy Croft, the principal of the Princess Alice home, selected six of his pupils to travel around to various churches singing, performing charity concerts and ringing hand bells. I was lucky enough to be in this sextet and even played the sleigh bells in the House of Commons one year! This was extremely gratifying and everyone involved felt very important. While the orphanage was Methodist based, it wasn’t too strict and did not push any particular religious beliefs upon us. I gained some insight into religion and formed some moral beliefs and guidance as a result of my time there. I even signed ‘The Pledge’ not to consume alcohol, though I may have strayed from that pledge slightly! Even so, I am pleased, and feel fortunate and grateful to have been raised in a moralistic and appropriate environment.

Some time later, I attended a Presbyterian church for a while and sang in the choir. While I no longer attend church, I still enjoy church music and take pleasure from the architecture and atmosphere of old churches. Perhaps I owe this to the good memories of the joyous times spent singing in them as a child.

Erika

This is a sample from one of our client's Biographies. This is just one section of a comprehensive 15,000 word narrative of her life.

When we arrived in Berlin we crossed over the street, Frederickstrasse, and suddenly, we were in the west. There was no distinguishable physical barrier at that time and we were happy to be there. However, from here, we had to go to a refugee camp as we had no documentation. The camp was an abandoned three storey Siemans factory which was damaged with no windows or doors and it was full of people in the same situation as us.

One Sunday, within three weeks of being there, Roswita and I went to the popular Wannsee Lake. At this time, the situation in Berlin began to deteriorate as we were right on the border of the East and the West. On our way back from the lake, there were tanks firing in the streets and one young boy was hit in the crossfire. When we returned to the refugee camp, we were told that from that point, no one was allowed to leave.

Even at thirteen years old, I knew that this was the start of something dramatic. Very soon, we were stranded on what was essentially a walled island. We were technically part of the West, surrounded by the Russians from the East.

There were approximately 5000 of us in the camp, and our beds were triple metal bunks. We had to go to the cellar and make our own mattresses with hay and straw. I befriended a little boy in the camp and we would run around and play together until he died as a result of tuberculosis. This was the cause of great concern that such a contagious disease was apparent in the camp. Other people committed suicide after they learned of the loss of loved ones. It was a terrible time.

My sister and I were at the age where we were still growing, and we started to grow out of the clothes we had left Ditfurt in. My grandmother however, resilient and capable, always found a way to provide for us. With her expert cooking skills, she soon began work in the refugee kitchen and was quickly promoted to kitchen foreman. With the small amount of money that she earned, she was able to buy us underwear and other essentials.

At one point, security dogs discovered that a tunnel had been dug under our refugee camp and had been packed with explosives. Due to the fact that none of the refugees had any papers, the authorities were strict about knowing who everyone was and making sure that were no spies amongst us. Understandably, there was panic in the camp and everyone was trying to leave. Every plane in the area was flying out, whether a privately piloted aircraft or a commercial flight. When there were spare seats, families within the camp were often able to take them, sometimes having to evacuate with just two hours notice.

As I was only thirteen at the time, I should have been on my grandmother’s passport, but when we applied for official papers, there must have been a mix up with my sister’s age and I was given a passport stating that I was fifteen. As a result, I was able to get a job arranging and organising for the appropriate paperwork to be provided to the refugees.

Allan Batchelor

This is a sample from the first three pages of Allan Batchelor's Biography. It continues as a comprehensive 9000 word narrative of Allan's achievements and personal reflections of both his family and business life.

If you were to ask Allan Batchelor’s family and friends what type of person he is, they would tell you that he is reliable, responsible, talented, a good listener and a great mate. Allan’s affable nature always shines through in the stories recounted of him. The people that know and love Allan will agree that he is known to enjoy a good lunch with a drink in hand, but after immediate consideration, it will be evident that what Allan really deserves to be recognised for is his uncompromising willingness to assist his community. This has endeared him to many people on his varied path between Goulburn and the Gold Coast.

Allan James Batchelor was born in the midst of bushfires on January 6, 1939 in Nabiac, a small town in the Wallamba district, situated on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales. Described today as a ‘vibrant rural village,’ in 1939 it was a small town focused on the dairy and timber industries, which had been settled for less than 80 years.

Allan’s family were members of the Church of England and he and his siblings were christened in the church. Allan was named after his mother’s cousin who had been a soldier in the Second World War. James was the name of Allan’s father and the middle name of his grandfather.

His father, James Cunningham Batchelor, was born on the February 10, 1902 in Coolongolook. He lived on a farm, and as the eldest of three boys, it was his duty to rise early, harness bullocks to a wagon and travel long distances in order to fell timber and transport the logs home. As a child, Allan was fascinated as to how his father had managed to load these sizeable logs onto the wagon, until James (Jim) explained that he had trained the bullocks to load them. While not an easy task, Jim would manipulate the bullocks to pull the logs towards the wagon and up a ramp he had constructed. Returning to the family’s dairy farm late at night, he had little time for anything else, and as a result, he was relatively uneducated.

Allan’s mother, Mary Ann Griffis, was born on November 20, 1906 in Willina. She too was raised on her parent’s farm and, as was customary at the time, was involved with such duties as cooking, cleaning and supervising children from neighbouring farms. Mary, whom Allan and all of his siblings had a great affection for, also had little education and was schooled for only a few years. She was however, a fantastic mother, a wonderful cook and housekeeper.

Mary had three brothers and three sisters. One of her sisters and two of her brothers were eventually called upon to serve in the Second World War. Most of Allan’s relatives stayed to work on their respective family farms during the war but he used to love hearing the tales of his relative’s that served for their country. While war often evokes tumultuous memories, many people that went to war had previously led such simple lives. In many respects the war brought different, often enjoyable, experiences of travel and interaction into their lives.

Mary and Jim met at a dance one Friday night in Coolongolook when they were both in their early twenties. It was quite a distance from their respective farms and proved a challenge to get there. They also attended the popular dances at Willina and Bunya and people would arrive from neighbouring towns in sulkies, a type of horse drawn carriage. Mary and Jim married in their early twenties, and made the bold decision to leave their family farms and live in Nabiac.

Jim was forced into leaving the bullock teams because of the lack of timber in the area. This was also a motivation to leave Coolongolook. At the outbreak of the Japanese War, Jim travelled to Townsville in order to work on the construction of the large Air Force base which was to be used by US air force aircraft. The work was tough and it kept him away from home for long periods of time. When he arrived back in Nabiac he was able to use his skills, in particular working on bridges, during his employment with the Manning Shire Council.

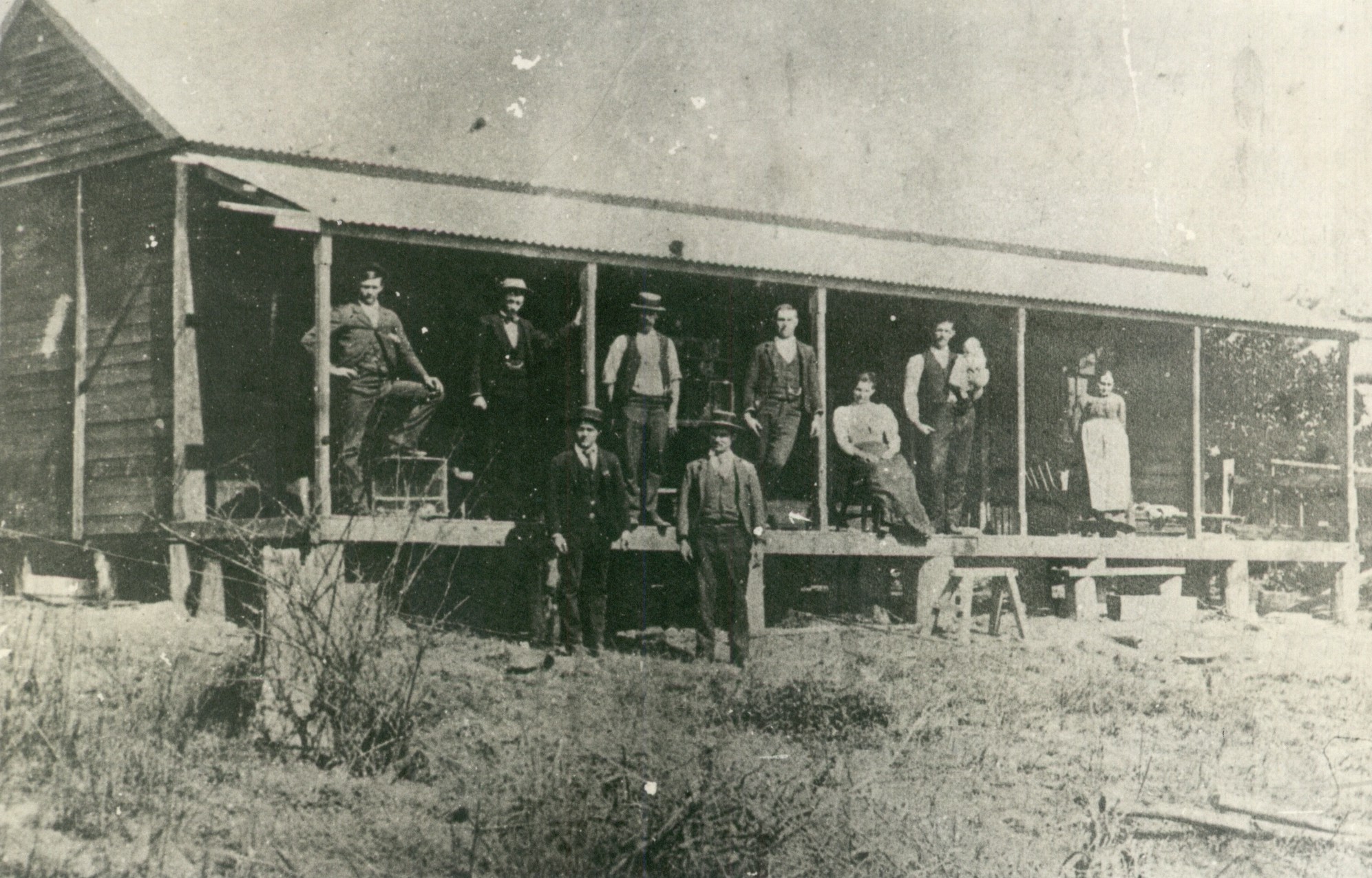

Images:- Allan, five and half years old in 1944 with his mother Mary, elder brother Keith, older sister Joyce, younger sister Ruth and baby brother Kevin. Shirley was not yet born.

- The Batchelor family homestead, Coolongolook 1900 Right to Left: Great Grandmother: Elizabeth Batchelor, Andy Batchelor with baby: Lill Huckett, Mrs Huckett, Jim Batchelor, Henry Huckett, Grandfather: Daniel Batchelor, Bill Batchelor, Thomas Batchelor.